A World of Meaning in "A World of Difference"

by Michael Martin DeSapioDuring its initial season (1959-60), The Twilight Zone introduced the public to its fantastical world by way of a series of superb, paradigmatic episodes. Writer Arlen Schumer has called them "Ur-Twilight Zones"—Ur being the German prefix denoting "primitive" or "original." Episodes such as "Walking Distance," "Perchance to Dream," "Mirror Image," "A Stop at Willoughby" and "The After Hours" are Twilight Zones par excellence, setting a pattern and a standard for subsequent installments. In them, such quintessential TZ themes as alienation, nostalgia for the past, the fragility of personal identity, and the thin veil between the real and the unreal are explored in ways which would resonate throughout the rest of the series' run—and in our popular culture ever since.

"A World of Difference" (first aired on March 11, 1960) also undoubtedly qualifies as an Ur-Twilight Zoneepisode. Richard Matheson's tale tells of an ordinary businessman who goes to his office one day only to discover that his life is a movie in which he is starring. This simple premise leads to a half hour fraught with high-voltage anxiety and disorientation. Like many Twilight Zones, "A World of Difference" is receptive to any number of interpretations, and unraveling the possible meanings adds to the pleasure of this archetypal episode.

"You're looking at a tableau of reality, things of substance, of physical material: a desk, a window, a light. These things exist and have dimension. Now this is Arthur Curtis, age thirty-six, who also is real. He has flesh and blood, muscle and mind. But in just a moment we will see how thin a line separates that which we assume to be real with that manufactured inside of a mind."

Our protagonist is (or so it would seem at first) Arthur Curtis, a successful business executive who is looking forward to going on vacation to San Francisco with his wife this weekend. Upon entering his workplace and greeting his secretary, Arthur repairs to his office to make a phone call, only to discover that the phone doesn't work. Suddenly he hears a voice exclaiming "Cut!" and, turning around, realizes that his office is actually the set and sound stage of a movie studio and that he is surrounded by a director and his crew.

Our protagonist is (or so it would seem at first) Arthur Curtis, a successful business executive who is looking forward to going on vacation to San Francisco with his wife this weekend. Upon entering his workplace and greeting his secretary, Arthur repairs to his office to make a phone call, only to discover that the phone doesn't work. Suddenly he hears a voice exclaiming "Cut!" and, turning around, realizes that his office is actually the set and sound stage of a movie studio and that he is surrounded by a director and his crew.

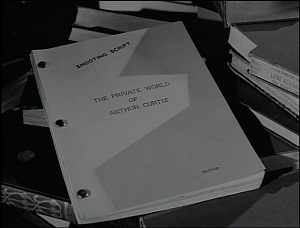

Everybody tells him that the person he thought he was—Arthur Curtis—is simply a character in the movie he is making (The Private World of Arthur Curtis), and that he is in reality Gerry Raigan, an alcoholic actor with a shrewish wife whose career is on the wane. Arthur/Gerry fights to re-establish his former identity. At his peak moment of despair—as the "stage set" of his office is being dismantled by the movie crew—his former world is suddenly restored as an answer to his prayer. Filled with relief and gratitude, Arthur/Gerry picks up his plane tickets from his secretary and departs on vacation with his wife. Meanwhile, on the abandoned set of The Private World of Arthur Curtis, Gerry's agent Brinkley wonders what happened to the star.

Rod Serling's opening narration informs us that one of the sides to this story is "manufactured inside of a mind." But which one? Who is our protagonist, really—Arthur Curtis or Gerry Raigan? According to the first interpretation—assumed by the opening narration and scene—our protagonist is Arthur Curtis, the happily married and self-possessed executive. The sudden invasion of the new reality of Gerry Raigan, then, represents the collision of two parallel worlds. By doggedly holding fast to what he believes to be the truth, Arthur finally breaks through the stranglehold of Gerry's world and returns to his rightful world.

Rod Serling's opening narration informs us that one of the sides to this story is "manufactured inside of a mind." But which one? Who is our protagonist, really—Arthur Curtis or Gerry Raigan? According to the first interpretation—assumed by the opening narration and scene—our protagonist is Arthur Curtis, the happily married and self-possessed executive. The sudden invasion of the new reality of Gerry Raigan, then, represents the collision of two parallel worlds. By doggedly holding fast to what he believes to be the truth, Arthur finally breaks through the stranglehold of Gerry's world and returns to his rightful world.

According to the second interpretation, our protagonist is harried Hollywood actor Gerry Raigan, who has sought escape from his miserable life by schizophrenically inhabiting the world of his movie character, Arthur Curtis. On this view, the ending consists of Gerry eloping with his co-star—in a sense, willing the fictional life of Arthur Curtis into existence. Serling's closing narration strongly implies that Gerry has died, or left the earthly realm—jetting off to heaven, perhaps. Alternately, "exit from life" could be taken to mean "escape from the stresses and turmoil of life in the modern world."

Duality is the operative theme of the episode, present in its very opening shot: as our protagonist emerges through the glass-paned door of his office, we briefly see a superimposed double image: the real Arthur Curtis and his reflection. The duality is subsequently played out as a clash of two different lifestyles—the placid bourgeois life of the suburban family man (Arthur Curtis) and the chaotic "Hollywood" life of the star actor (Gerry Raigan). The Hollywood star undone by marital difficulties, alcohol or drugs was a real-life character type familiar to postwar audiences—the antithesis of the era's ideal of domestic tranquility.

Duality is the operative theme of the episode, present in its very opening shot: as our protagonist emerges through the glass-paned door of his office, we briefly see a superimposed double image: the real Arthur Curtis and his reflection. The duality is subsequently played out as a clash of two different lifestyles—the placid bourgeois life of the suburban family man (Arthur Curtis) and the chaotic "Hollywood" life of the star actor (Gerry Raigan). The Hollywood star undone by marital difficulties, alcohol or drugs was a real-life character type familiar to postwar audiences—the antithesis of the era's ideal of domestic tranquility.

"A World of Difference" critiques the artificiality of modern life, in which fiction, escapist entertainment, and role-playing of all kinds are so pervasive. Arthur realizes something is amiss the moment he picks up his phone and realizes it is only a prop. A moment later, he stares flabbergasted as a couple of stagehands walk outside his office ledge casting shadows on the cityscape, thus revealing it to be a backdrop. In this surreal moment, even the verisimilitude of TZ is cast into doubt! Arthur's fourth wall has been removed, and as stage crew encircle him suspiciously, we are led with Arthur into a vortex of confusion and menace.

The duality of the two worlds (Arthur's versus Gerry's) is also covert social commentary. During the Cold War the U.S. and the communist world were often thought of as "parallel worlds." And indeed, compared with the tranquil domestic world of Arthur Curtis—equivalent, perhaps, to the "American way"—the world of Gerry Raigan seems totalitarian, devoid of freedom, constantly monitored. The episode reflects the anxiety of many during that era that the security of the American way of life could be snatched away at a moment's notice. "I don't know where I am, and yet I must! I live here!" exclaims Arthur/Gerry as he drives bewildered through his suburban neighborhood unable to find his home.

The duality of the two worlds (Arthur's versus Gerry's) is also covert social commentary. During the Cold War the U.S. and the communist world were often thought of as "parallel worlds." And indeed, compared with the tranquil domestic world of Arthur Curtis—equivalent, perhaps, to the "American way"—the world of Gerry Raigan seems totalitarian, devoid of freedom, constantly monitored. The episode reflects the anxiety of many during that era that the security of the American way of life could be snatched away at a moment's notice. "I don't know where I am, and yet I must! I live here!" exclaims Arthur/Gerry as he drives bewildered through his suburban neighborhood unable to find his home.

As Arthur/Gerry stares at a pair of blank photo frames on his desk—his wife's and daughter's identities having been canceled out along with his own—he prays desperately: "Don't leave me here!" Immediately a quasi-divine illumination lights up his face, and his wife appears in the doorway. Marion Curtis is a plain, gentle woman—a stark contrast to the pitiless "harpy," Nora Raigan. Arthur, hearing ominous echoes of the movie studio crew, insists they leave right away on their vacation—"I just don't want to lose you." Thus the episode delivers a message about appreciating and guarding one's blessings (freedom, peace) which are in danger of disappearing when one least expects it.

The episode's title bears consideration. Among the dictionary definitions of "difference" we find: "dispute or quarrel" and "disagreement in opinion." Thus, in addition to the title's obvious meaning—there is a "world of difference" between the lives of Arthur and Gerry—we have also the implication that our world is a world of difference—i.e., of conflict and strife. As Brinkley declares, "sometimes I'd like to escape myself. Away from this turmoil, to some simpler existence." The significance of the character of Brinkley (the name suggests that Arthur/Gerry is on the "brink" of disaster) is to show that even in this harsh world there is some goodness.

Acting, directing, cinematography and music combine to make "A World of Difference" one of The Twilight Zone's most compelling episodes. Howard Duff, with his perpetually haunted look, renders the numbed bewilderment of Arthur/Gerry palpable in every frame. Eileen Ryan's delightfully strident performance as Nora Raigan, David White's consolingly sympathetic one as Brinkley, and Gail Kobe's perky turn as Arthur's secretary fill out the cast. Costumed in an incongruous and menacing pair of black gloves, Ryan throws herself wholeheartedly into her vicious role.

The music score was composed by Nathan Van Cleave and features the theramin, an electronic instrument whose emotive, wailing tones adorned many a sci-fi film in the 1950s. The theramin's music is ramped up to fever pitch during the sequence when Arthur/Gerry speeds down the highway to the movie studio to reclaim his identity.

The music score was composed by Nathan Van Cleave and features the theramin, an electronic instrument whose emotive, wailing tones adorned many a sci-fi film in the 1950s. The theramin's music is ramped up to fever pitch during the sequence when Arthur/Gerry speeds down the highway to the movie studio to reclaim his identity.

The very best Twilight Zones invite the viewer to choose his or her own interpretation, and "A World of Difference" is one of these. The questions multiply after viewing. Was Arthur Curtis' experience nothing but the daydream of a bland office denizen who likes to imagine alternate scenarios to his life? Are we all, in our lives, playing stereotypical roles that were scripted for us by custom or society? And what of the redemptive power of art—can it help us escape from the harsh realities of earthly existence? All these questions are only a taste of the world of meaning to be discovered in this popular episode. As with Arthur Curtis, the sky is the limit.

"The modus operandi for the departure from life is usually a pine box of such and such dimensions, and this is the ultimate in reality. But there are other ways for a man to exit from life. Take the case of Arthur Curtis, age thirty-six. His departure was along a highway with an exit sign that reads, 'This Way To Escape.' Arthur Curtis, en route to the Twilight Zone."

To contact Michael, send email to michaelmartind@gmail.com