"Ninety Years Without Slumbering": A Case for the Defense

by Michael Martin DeSapioThis essay is dedicated to my grandmother, Elizabeth Rienzo Colella.

"My grandfather's clock was too large for the shelf,

So it stood ninety years on the floor;

It was taller by half than the old man himself,

Though it weighed not a pennyweight more.

It was bought on the morn of the day that he was born,

And was always his treasure and pride;

But it stopp'd short -- never to go again --

When the old man died.

Ninety years without slumbering

(tick, tock, tick, tock),

His life's seconds numbering,

(tick, tock, tick, tock),

It stopp'd short -- never to go again --

When the old man died."

"My Grandfather's Clock" by Henry Clay Work (1832-1884)

As time wore on, The Twilight Zone's clock gradually wound down, so say many fans of the show. By the fifth and last season (1963-64), many themes covered in earlier seasons were retreaded and outstanding episodes were fewer. One episode from this season that has been unfairly overlooked is "Ninety Years Without Slumbering", written by Richard De Roy from a teleplay by George Clayton Johnson. "Ninety Years" tells the story of an old man, Sam Forstmann, who believes that he will die if his grandfather clock stops ticking; Sam grapples with this superstition and eventually overcomes it. While acknowledging Ed Wynn's endearing and artless performance as Sam, many fans find the plot illogical and the ending disappointing. They cite the fact that De Roy changed Johnson's original ending for the story (in which Sam dies), to Johnson's disapproval; in fact, Johnson demanded that his name not be associated with the televised version. It is my conviction that many of the common objections to "Ninety Years" are based on false expectations and that the changed ending is satisfying in its own way. If we set our preconceptions aside and enjoy the episode on its own terms, we will discover in it a touching meditation on time, tradition and mortality. "Ninety Years Without Slumbering" is among The Twilight Zone's most attractive episodes.

The episode was inspired by the children's song "My Grandfather's Clock," written in 1876 by the American abolitionist and songwriter Henry Clay Work. The song uses a clock as the symbol of the life of a human being: "it was bought on the morn of the day he was born" and accompanies him through childhood, marriage, maturity, and death. "My Grandfather's Clock" is woven like a leitmotif into "Ninety Year's Without Slumbering": Sam sings it to himself as he works on his clock; its melody serves as the basis for Bernard Herrmann's musical score; and, of course, the episode's title is derived from it.

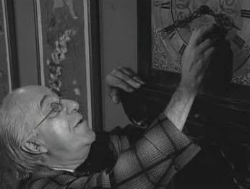

Sam Forstmann is an old man with an eccentric hobby: a constant preoccupation with his grandfather clock. The name Forstmann suggests the obvious: the forest, where wood is culled; Sam--a retired clockmaker himself--probably comes from a family of German craftsmen. The idea of tradition and craftsmanship, as well as family bonds, is an important component of "Ninety Years Without Slumbering". When we first see Sam, he is cheerfully tinkering with the clock in his bedroom; downstairs in the living room, his granddaughter, Marnie, and her husband, Doug, discuss Sam's condition. Marnie is expecting her first child, and this fact combined with her grandfather's obsession is creating tension in the household. Marnie, hesitant to confront Sam, is lovingly but firmly urged by Doug to face facts and discuss the situation. One of the strengths of "Ninety Years" is its human element, and Marnie's conversation with Sam shows the tender relationship between the two; even the way they are costumed (in a similar plaid pattern) underlines the bond between them. Sam assures Marnie that "the clock is ticking along nicely now" and promises to resume eating (the obsession has taken away his appetite).

Clocks are used as a visual element throughout the episode; several scenes end with a dissolve into a closeup shot of a grandfather clock pendulum, and at the episode's climax there is an imaginative double-exposure sequence in which a swinging pendulum is superimposed on the action. A telling cinematographic moment occurs in the next scene as Sam lies sleeplessly on his bed at night. When the camera cuts from Sam to the grandfather clock, we see Sam's reflection in the clock's glass plate. This single shot sums up the unspoken truth about Sam's obsession with the clock: it is actually about Sam himself. As he remarked earlier to Marnie:

"Of course, with a clock as old as that, well...you're bound to run into problems, you know. Just like old people...."The clock was given to Sam the day of his birth; his father and grandfather told him that when the clock ran down, he would die. Whether a superstition or merely a whimsical encouragement to hard work, this belief has taken over Sam's life. His cheerfulness and cocky self-assurance mask his deep anxiety about his own mortality; by fussing over his clock, he is struggling to forestall death. Sam is caught in a vicious cycle: plagued with insomnia (like his father before him), he seeks therapeutic relief through working on the clock, which in turn feeds the obsession. He is reduced to pleading with the clock as with a human being: "Please! Please don't stop. I'll never forget to wind you again. I promise!" In short, "My Grandfather's Clock," for Sam, has become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

************

"In watching its pendulum swing to and fro,

Many hours had he spent while a boy;

And in childhood and manhood the clock seemed to know

And to share both his grief and his joy.

For it struck twenty-four when he entered at the door,

With a blooming and beautiful bride;

But it stopped short -- never to go again --

When the old man died.

Ninety years without slumbering

(tick, tock, tick, tock),

His life's seconds numbering,

(tick, tock, tick, tock),

It stopp'd short -- never to go again --

When the old man died."

Eager to help Sam, Doug arranges for him to visit a psychiatrist friend of his, Dr. Mel Avery. Sam scoffs at the idea of letting someone "tinker with his head" (a telling metaphor), but agrees to go in order to show "who the crazy one really is." The scene with Dr. Avery shows a clash of generations, with the older clearly holding its own with the younger. Dr. Avery represents the modern world of psychoanalysis; Sam, the older values of familial love and craftsmanship. Remaining firmly in control, Sam eludes any attempt by Dr. Avery to find out what makes him tick. As the scene opens, he is telling the doctor about his childhood. He speaks of his parents' "unfashionable" love for each other, a love which resulted both in his life and in the creation of the clock. The bond between Sam and the clock deepens: we realize that Sam, just like the clock, is a "family heirloom", worthy of being preserved. Anticipating Dr. Avery, Sam denies that he sees the clock as a living person, but is unshakable in his conviction that he'll die when it stops ticking. Dr. Avery advises Sam to get rid of the clock; somewhat bitterly, Sam interprets this as an ultimatum: "Either the clock goes, or I go." After Sam leaves (explaining that "your time's expensive; mine's free"), the young doctor, clearly flummoxed, pounds his fist with mild frustration on his table clock. It is a small, generic art deco model, the antithesis of Sam's grand, handcrafted Victorian timepiece.

Yet Dr. Avery's advice has not fallen on deaf ears. In the next scene we see Sam overseeing the transferal of the clock downstairs by some professional handymen. Marnie and Doug come home from an evening on the town to find the clock parked in front of an abstract painting in the front hallway. The juxtaposition of the Victorian clock with the modernistic painting suggests, again, the generational clash. Doug is not happy: "it sticks out like a sore thumb." The compromise having failed, Sam decides to take a more drastic step, which will be his point of no return. He sells the clock to the next-door neighbors, securing permission to come around and wind the clock every other day. But two weeks later--as would inevitably happen--the neighbors go on vacation and Sam is no longer able to visit his "friend." Now Sam knows it's all over; as soon as the clock winds down, he will die. Ruefully, he admits that he has only been forestalling the inevitable: "Two weeks of borrowed time. I should be grateful."

************

"It rang an alarm in the dead of the night --

An alarm that for years had been dumb;

And we knew that his spirit was pluming for flight --

That his hour of departure had come.

Still the clock kept the time, with a soft and muffled chime,

As we silently stood by his side;

But it stopp'd short -- never to go again --

When the old man died.

Ninety years without slumbering

(tick, tock, tick, tock),

His life's seconds numbering,

(tick, tock, tick, tock),

It stopp'd short -- never to go again --

When the old man died."

Sam's final battle is about to begin. Unable to stop thinking about his "dying" grandfather clock, he sneaks out of the house at night with his toolkit. After breaking the neighbors' window in a desperate attempt to reach the clock, he is escorted back to his house by a passing patrol officer. Next we see Sam lying in bed, utterly resigned to his fate: "It's better this way. It has to come sometime and I want it to come for me here." The grandfather clock breathes its last. At this point the ending that we have been expecting is thwarted, and Sam enters the Twilight Zone. Sam's spirit separates from his body and stands at the foot of his bed, summoning him to death: "Sam, old friend, it's been a good life. But now it's time to go." Sam, so cheeky and quick-witted with Dr. Avery, now puts his wits to work with a new adversary: himself. What Dr. Avery was not able to achieve through psychoanalysis--exorcise Sam's inner demon--Sam will now achieve by his own willpower. Ed Wynn's other "Twilight Zone" role, in Rod Serling's episode "One for the Angels", had him facing off with a figure of Death; here, he is facing his own weaker side, the side that portends spiritual death. In the following exchange, the hollowness of superstition is laid bare:

"Have you forgotten what your father told you? And your grandfather? [...] Didn't they always tell you that when the clock winds down, you'll die?"

"Yes. And you know something? I used to believe that stuff".

"You should have! They told you often enough."

Superstition, in other words, offers no justification for itself other than bald repetition. Sam, thanks to his contact with Dr. Avery ("I've been to a psychiatrist," he exclaims gleefully), is able to reclaim reason: "You're just a figment of my imagination! Why, I can see right through you; I repeat: I don't believe in you. Therefore you don't exist. Right?"

At these words, the "spirit" vanishes into thin air; Sam has vanquished his demon. He puts his glasses aside, lies down with a self-satisfied smile and--presumably for the first time in a long while--drifts into a peaceful slumber. When Marnie returns later in the night to check on him, he is a new man: jumping up from bed, he deflects attention from himself, exclaiming that "the thing to worry about is that great-grandchild of mine" and taking Marnie downstairs "for a good cup of hot chocolate." (Perhaps Sam will always be a bit of an insomniac, but this action shows that he will now spend his time serving his family--not in self-absorbed clock-tinkering.) Sam declares openly that the clock had been on life-support for the past forty years and that it stopped ticking for the last time just a few moments ago. He explains that it had taken "everything I ever learned in clock making just to keep it going," which suggests that he had been hanging on tenuously to his delusion all that time.

"And a strange thing happened, Marnie. When that clock died, I was born again."An almost Easter-like sense of renewal and rebirth accompanies Sam's awakening. He has been given extra time, a new lease on life.

George Clayton Johnson's original story ended quite differently: Sam died, fulfilling the superstition and making way for the birth of his great-grandchild. This almost tragic ending expresses the elemental, pagan worldview: man as subject to time and nature. Richard DeRoy's new ending introduces the Christian element of the miraculous and redemptive. Since we know how My Grandfather's Clock ends, and since this is The Twilight Zone, we expect Sam to die. When he doesn't die, we are genuinely, and joyfully, surprised. By wrenching Johnson's tragic conclusion to a comic one, de Roy paradoxically created a true Twilight Zone twist.

The prominence of clocks in "Ninety Years" points to the pervasive theme of time. Marnie's pregnancy and Sam's life both hinge on time. Too, the story points to the chain of time that binds human beings together in history. A total of six generations are involved in the story: Sam, who has memories of his grandfather, will live to play with his own great-grandchild. The episode seems to say that each of us is the sum total of the people, old and young, that we come in contact with during our life. Finally, "Ninety Years" suggests the reconciliation of the generations. During his verbal sparring with his spirit, Sam identifies with the new rather than the old: "You're from another generation! See, I live in the present. Live, I say!" We hope that Sam will, like his own father, live to ninety and reap the benefits of his long life.

"Ninety Years Without Slumbering" is one of the more human episodes in the Twilight Zone canon, and a far richer piece than it is given credit for. It is an affirmation of personal choice against determinism; it speaks to second chances, the continuance of life, and the chain that connects past, present and future; it celebrates the human spirit, family bonds, and the dignity and vitality of old people. And finally, it inspires us to become conservationists of that most precious natural resource--the gift of time.

"Clocks are made by men, God creates time. No man can prolong his allotted hours, he can only live them to the fullest - in this world or in the Twilight Zone."

To contact Michael, send email to michaelmartind@gmail.com